According to 2022 statistic, more than 674 millions of people live in Southeast Asia. They live in very vast area, because Southeast Asia stretches some 4,000 miles from northwest to southeast and encompasses 13,000,000 square km of land and sea. Within this broad outline, Southeast Asia is perhaps the most diverse region on Earth with hundreds of ethnic groups and languages.

Source: World Population Review

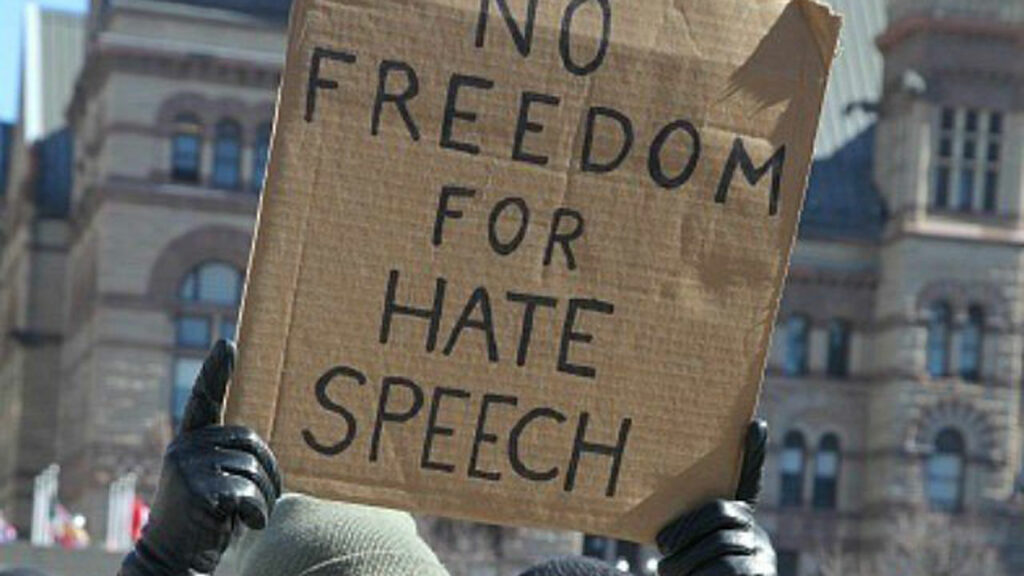

Some identity-based violence has occurred in the past and now the challenges are increasing due to the development of digital technology. This paper will seek for explanation on what challenges stand in the way of addressing the risk of online identity-based violence in Southeast Asia? By identifying these challenges, I hope this paper can help the State to take some safeguard to protect their populations from genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity, as stated under the UN General Assembly’s 2005 World Summit Outcome Resolution.

Source: Insider Intelligence

With the rise of internet access across Southeast Asia, where now over half of Southeast Asia’s population, around 53.9% or approximately 326.3 million in 2022 (Insider Intelligence 2022), online identity-based violence (or simply said online hate speech) has become new drivers of domestic conflict in the region. In a region rife with longstanding social tension, the growth of internet use has provided a new tool to inspire and coordinate hatred and conflict. Online hate speech often draw on historically-rooted social tensions, which many political elites choose to enflame rather than temper.

Take some examples.

Before the coup in February 2021 in Myanmar, political parties, candidates, and their supporters espousing Buddhist extremism deployed hate speech targeting religious minorities on social media in advance of the 2020 elections. During the campaign period, Muslim candidates faced attacks and threats online, while political parties fielding Muslim candidates were targeted as “not protecting race and religion.”

In Indonesia, during the regional election in Jakarta in 2017, the political elite and their supporters used one ethnicity as a candidate for Governor to win support. By equating political opponents as symbols of anti-Islam, they spread videos edited by Al Madina quotes via digital platforms. As a result, a wave of demonstrations was carried out to “save Jakarta” from the hands of non-Muslim.

Let’s not forget about what happened in 2017, where Muslim Rohingya genocide incite in Facebook by Myanmar’s military. A report by Reuters found more than 1,000 posts, comments, images, and videos attacking Rohingya and other Muslims on Facebook.

I highlight two key commonalities of online hate speech in this region. First, hate speech is political. In each country, religious, political, or military elites perpetrate, encourage, or benefit from hate speech and identity-based violence.

Second, hate speech and violence target minority groups, cleaving onto historically embedded conflict dynamics in Southeast Asia.

In the region, longstanding tension over the ethno-religious identity of the state has created persistent anxiety among the majority identity group about their status and safety. Although typically not grounded in reality, the majority’s paranoia creates a highly combustible setting in which even the smallest slight—real, perceived, or concocted—can result in violence against a vulnerable minority.

SAFEnet research in 2022, titled “Hate Speech in Digital Space“, confirms that online hate speech can occur for religious reasons (62%). Online hate speech often used to attack political opponents, dissent, and critic.

In response to these instances, several governments in Southeast Asia have expanded their powers to regulate online speech. For example, article 66d of Burma’s Telecommunications Act (2013) create new regulatory authority ostensibly designed to limit hate speech and disinformation. Indonesia create new digital policy under Ministerial Regulation 5 “MR5” (2020) and the new Penal Code (2022). However, critics have charged the governments with abusing these often vaguely worded laws to target political opponents and limit dissent.

Technology companies have also attempted to control harmful speech on their platforms. Facebook, which has come under growing criticism, has enacted new community guidelines on hate speech, hired native speakers across Asia and created automated tools to monitor and remove content, changed product features, deactivated groups, and banned users. Still, the avalanche of content on Facebook produced in over one hundred languages makes the task of preventing or removing all violent and hateful content almost impossible.

Several underlying factors limit the effectiveness of governments’ and technology companies’ attempts to regulate online hate speech. First, even good-faith restrictions on online speech spark a debate about freedom of expression as the boundary between controversial opinions and violence-inducing hate is not always clear. Second, social media provides anonymity and accelerates the spread of information, which makes it inherently difficult to regulate. And third, political incentives undermine hate speech regulations in Southeast Asia. In the region, hate speech is effective at mobilizing people, and hate speech targeting minority groups is often popular. These two factors create a strong disincentive for politicians to control hate speech.

Therefore, to solve this problem requires a citizen-centered approach that can address this challenge from the bottom up. A citizen-centered and civil society-led initiatives have proved to be an important complement to new rules from governments and tech companies.

Now our organization lead some initiatives in regional level and national level. Through Southeast Asia Collaborative Policy Coalition (SEA CPC), we develop a collaborative work with tech platforms to develop new tools and policies to tackle online hate speech, content moderation, and disinformation.

And through Indonesia CSOs’ Digital Democracy Resilience Network, we are currently working the same to mitigate the upcoming election in 2024.

These initiatives are in line with other works done so far by CSOs, who is doing digital literacy workshop to teach citizens how to recognize and report misleading content and hate speech. Also with fact checking groups who systematically examining, reporting, and rebutting online falsehoods that can lead to violence.

Some example has proven working in national level, like civil society groups in Burma have successfully combatted online hate speech by documenting and reporting its instances to social media platforms. In advance of the 2020 Burma elections, civil society groups successfully pressured social media platforms to develop new tools and policies to reduce hate speech and rumors targeting religious and ethnic minorities. Also Social Media Council in Ireland that also able to help tech platforms to develop new tools to tackle the ongoing online identity-based violence.