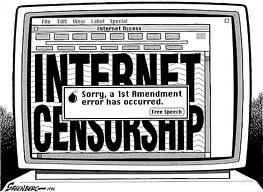

Responding to public outcry accusing the government of infringing free speech rights, the Communications and Information Ministry reopened on Tuesday access to 22 websites the National Counterterrorism Agency (BNPT) had condemned for promoting radicalism in the country.

The government decided to block the websites following the circulation of web-based Islamic State (IS) movement propaganda that authorities believed was helping IS recruit support in the country.

Rights groups have said the anti-terrorism measure could backfire, setting the stage for crackdowns on critics of the government.

Earlier, the ministry blocked access to a host of websites, including arrahmah.com, voa-islam.com, dakwatuna.com, kafilahmujahid.com, an-najah.net, muslimdaily.net, hidayatullah.com, salam-online.com, known for their incendiary content. As of Tuesday evening, all the sites were back online.

Ahmad Fuad Fanani of the Maarif Institute for Culture and Humanity said that rather than blocking the websites, the government should educate the public about the information on the Internet.

“We have to admit that some of the blocked websites encouraged hate speech, but some of them were quite moderate. I think the decision to block the websites was a rushed decision,” said Fuad.

He conceded that a number of Islamist websites espoused extremist ideology, but added that by allowing the government to ban them unilaterally, the freedom of speech for all citizens was threatened.

“If blocking a radical website is unavoidable, then authorities should first summon its representatives to seek clarification. If there has been a violation of rules then it should be reprimanded. If the party rejects the reprimand, then the government could go ahead and close it,” Fuad said.

Wahyudi Djafar of the Institute for Policy Research and Advocacy (ELSAM) blasted the blocking of the Islamist websites, saying it was a “repressive” measure.

“Without a strong legal framework and accountable procedures, it is nothing but a repressive measure,” he said.

The 2008 Information and Electronic Transactions (ITE) Law describes the kind of Internet content that can be censored, but does not stipulate the proper procedures for doing so.

Two other regulations, the 2008 Pornography Law and the 2014 Copyright Law, authorize bans on pornographic content and materials violate copyrights, respectively.

The Communications and Information Ministry maintained it had the right to block the 22 websites as mandated by the Ministerial Regulation No. 19/2014 on negative content. The regulation was drawn up to implement Law No. 11/2008 on electronic information and transactions (ITE).

“The ITE Law bans illegal content, which includes [hateful] information on SARA [tribal affiliations, religion, race and societal groups] and those responsible for publishing the content can be punished. What about these websites? How could we allow such negative content to circulate? This is where the regulation comes in,” an advisor to Communications and Information Minister Rudiantara, Henri Subiakto, told The Jakarta Post on Tuesday.

He said the government was justified in its attempts to curb negative content in order to prevent the spread of radicalism.

“Other countries that are totally free and liberal actually could do nothing against the propaganda coming from radical groups. For example, the UK, where its youngsters have gone Syria [to join IS],” Henri said.

The BNPT said that only websites that promoted religious-based violence could be blocked.

“The websites contain elements of radicalism, such as declaring that other religions, beliefs and people are infidel. Also, they want to make drastic changes by employing violence in the name of religion,” BNPT spokesperson Irfan Idris said on Tuesday.

Chief editors of some of the banned sites denied the accusations.

“We feel that we have never done such things. There has been no protest from our readers about calling some people infidels,” hidayatullah.com chief editor Mahladi said.

Source: Jakarta Post